Have you ever come across of big ball of mud in the system that you work on? Have you ever wondered how it ended up like this? I bet that no one gets up in the morning and thinks “I will get to work to create a huge mess today”. However, there was at least one huge mess in the majority of the software projects I have worked on. What causes this?

A typical scenario is that a piece of code starts off simple and innocent, but we always have to keep in mind the bigger picture. The architecture of the system. The code design. It is an integral part of our day to day work. Failing to pay attention to it, can start a chain reaction. One that leads to a big ball of mud.

Let’s use a simple case from a real world project and study the risks that we introduce by not thinking ahead and designing the code carefully.

A case study

Instead of creating an example around trivial, overused, fictitious domains, consisting of either shapes or animals, I believe that a real case will enable us to apply the principles to a professional context, which is key to a better understanding. This is why I chose to focus on a problem that I faced a while ago on work. Of course, I have simplified it quite a lot in order to remove noise and focus on the essential parts.

The problem

Let’s assume that we work on an android application and the task in hand is the validation of a form, which the user should fill in. So, the form may contain fields for the user to fill in her name, phone, e-mail address, age, gender etc and before processing the information, we should validate that it is correct. In some cases validation may be redundant with the use of the appropriate UI elements (for instance, we should not validate gender if we use a radio button for it), but for some other cases (e.g. e-mail or phone number) we should definitely validate the user input.

For the sake of simplicity, we will not occupy ourselves at all with android, the UI and the way that we collect the data. We assume that we already have a list of View objects (in android all UI elements derive from View). We further assume that all these objects have a tag, which we can retrieve using a getter, denoting the view’s input type (e.g. Email or Phone) and a getter to retrieve the text of the view (in reality things are a bit more complicated, but we make these assumptions because the point of this post is not to delve into android UI details).

Therefore, all we have to do is to implement a module that receives this list of View objects and validates the input data that they hold.

A first implementation

This sounds like a reasonably straightforward task and agile teaches us that we should go with the simplest thing working. Therefore, a first implementation of the solution could look like the following:

for (View view : formViews) {

if (view.getTag() == "Email")

// Apply email validation logic

else if (view.getTag() == "Phone")

// Apply phone validation logic

}

Now, this is a very succint piece of code and if we care enough to extract some methods for the if block conditions, it could even be readable and retain the same level of abstraction.

However, there are things that we should be dissatisfied with. Feel free to take some time to reflect before continue reading. Which could these issues be? What troubles you with this piece of code?

Architecture

Let’s not fool ourselves, we’ve all written code like this (at least I know that I have), but as we grow more experienced, we should identify shortcomings and take the pains to address them.

Apart from some minor issues, like the fact that we should extract some constants from these magic strings and the ones that we mentioned above (extracting methods for the the if block conditions etc), which are easy to amend and would not cost that much in the long run even if we neglected them, there is a serious concern in this piece of code.

Let’s think for a moment what would happen if a new field was added to the form. A field which did not exist before and therefore for which we hadn’t implemented any validation logic. Say a postcode field. How would we add support for this new field in our existing code?

Most probably we would add an extra else if block to handle the case of the postcode. However, that means that we would be modifying the existing code to add an extra feature. This sounds like an oxymoron, doesn’t it? When we want to add a new feature, we should add some code and not modify the existing code.

Of course, this case is simple and I bet you think “what could possibly go wrong with adding an extra else if block?”, but as we keep on adding more and more conditionals when requested to add a new field to a form, the code could grow quite complex. There could be functions that are used by more than one case, or even worse, there could be shared state. Perhaps we could reach to a point that by making a modification for one case, we accidentally break another case. According to Uncle Bob, that is a sign of great significance. The system is exhibiting the symptom of fragility.

Adding support for a new feature and accidentally breaking an unrelated feature is a dreaded situation. As software craftspeople, we should go to great lengths to avoid it. Therefore, let’s examine how we could shield our code from such problems.

The Open-Closed Principle

The Open-Closed principle (OCP) is the O of Uncle Bob’s SOLID principles (described in detail in Clean Architecture). As formulated by Bertrand Meyer in Object Oriented Software Construction, it states that

A software artifact should be open for extension but closed for modification.

Contradictory as it may sound, there’s a lot of wisdom in that sentence. Essentially, we should be able to extend the behavior of a module, without having to actually modify its code. That resembles a lot what we discussed earlier. When we want to add a feature (behavior), we should add some code instead of modifying the existing code.

Since this is a notoriously difficult to understand principle (perhaps due to the contradiction when articulated), let’s apply it to the input validation problem, that we analyzed earlier.

OCP compliant validation

Let’s keep in mind that the goal is to implement a validation module that can be extended without being modified. Let’s try to design it in such a way that implementing the postcode validation cannot affect the existing validation logic.

In order to achieve this, we should separate the high-level validation policy from the low level details. The former refers to the way we validate a set of data and the latter to the details of how we validate data for specific input fields (like e-mail, phone numbers and postcodes). Ideally, we would like the former to be agnostic to the latter, like the following:

formViews.forEach(view -> {

ViewValidator validator = ViewValidatorFactory.makeFor(view);

validator.validate(view.getText());

});

This reads like a nice algorithm. For every view, we get hold of an appropriate validator and apply its validate() method to the text that the view holds. Notice that we do not know how each specific field get validated. This is achieved by getting a Validator on runtime using the ViewValidatorFactory, but not knowing on compile time which one we will get on runtime. To achieve this, we need to create an interface like the following and have the factory returning objects deriving from this interface

public interface ViewValidator {

void validate(String input) throws ValidationException;

}

and implement it for every specific field that we need to validate, as follows

public class EmailValidator implements ViewValidator {

public void validate(String input) throws ValidationException {

// Actual email validation code omitted for brevity

}

}

and

public class PhoneValidator implements ViewValidator {

public void validate(String input) throws ValidationException {

// Actual phone validation code omitted for brevity

}

}

Now, all that’s left to glue it all together is to implement the factory that creates the validators based on the view.

public class ViewValidatorFactory {

public ViewValidator makeFor(View view) {

switch (view.getTag()) {

case "Email":

return new EmailValidator();

case "Phone":

return new PhoneValidator();

default:

return new DefaultValidator();

}

}

}

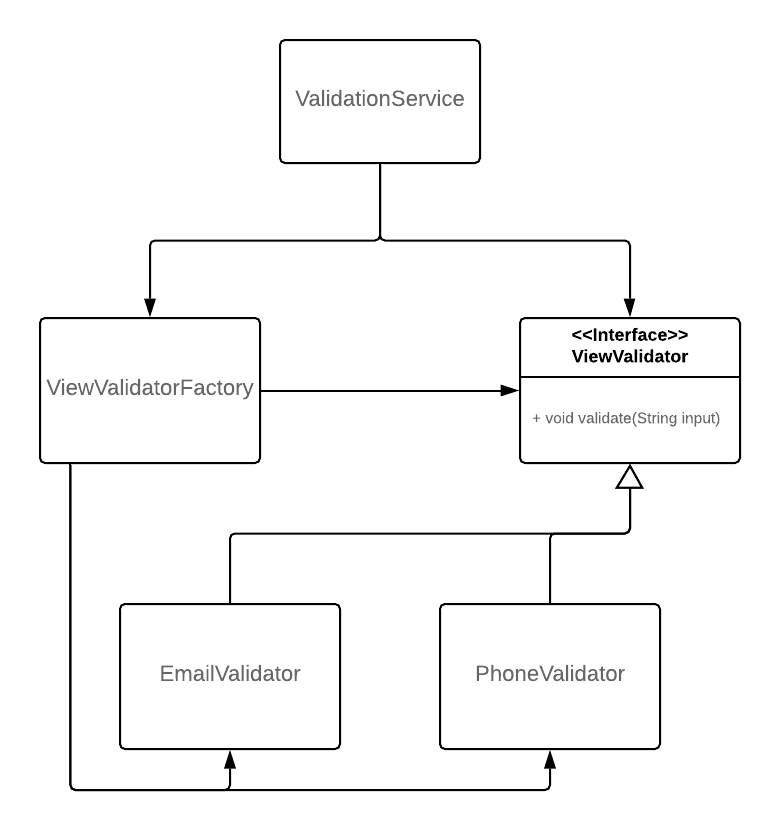

This design is depicted below, in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Validation compliant to the Open-Closed Principle

The ValidationService has a transitive dependency to the EmailValidator and PhoneValidator (which is a shortcoming that we should amend using an abstract factory to apply the Dependency Inversion Principle) and therefore will be recompiled when we add a PostcodeValidator, but other than that (which is harmless unless we have an architectural boundary between the two modules) the source code of the ValidationService and the rest of the validators will remain untouched, which means that we have solved the fragility issue, by provisioning for the addition of new fields (and therefore validation logic for them) in the future. In other words, there is no way to break the functionality of (e.g.) the EmailValidator by adding a PostcodeValidator.

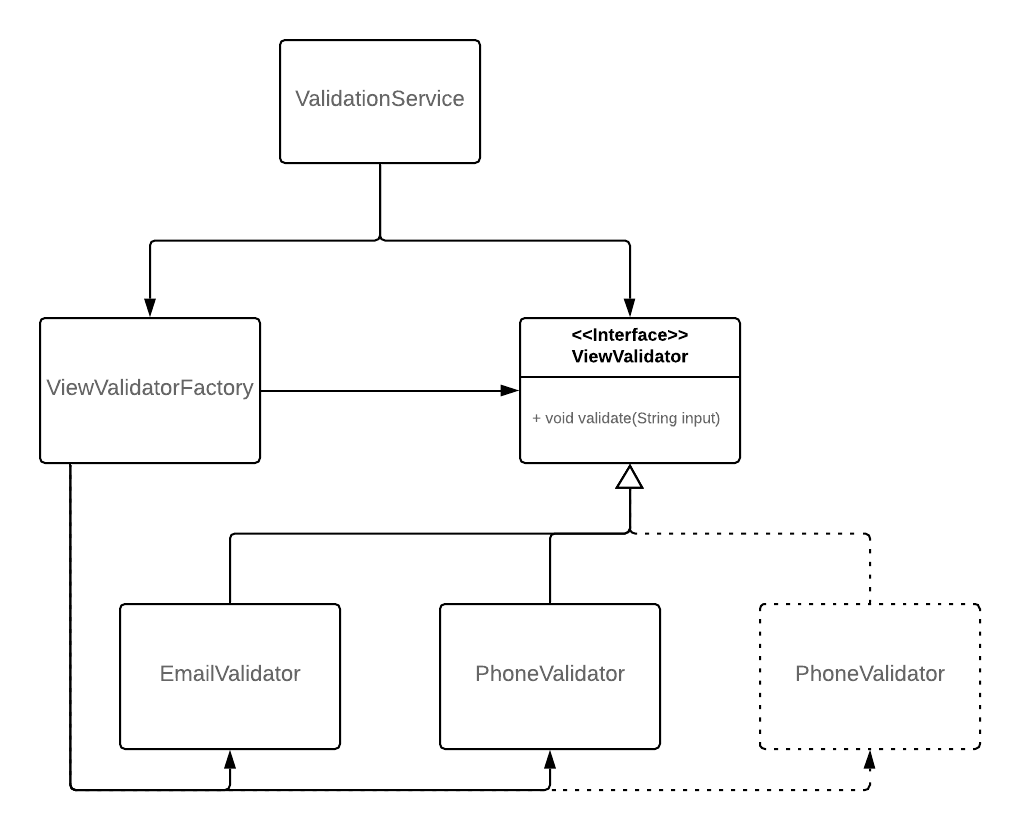

Indeed, Let’s consider what is needed to add validation for the postcode now. All we have to do is to create a new derivative of the ViewValidator, the PostcodeValidator and apply a minimal modification to the factory, to be able to create one for the appropriate view. The change is depicted in figure 1.2, denoted with dotted rectangles and arrows.

Figure 1.2: Adding a postcode validator to the existing implementation

In this way, we manage to extend the behavior of ValidationService without modifying it.

Iterative approach

Of course, presenting the code in its final state, like I did, may lead to a reasonable question. Did it just pop magically into my mind? What if I can’t think of the big picture all in once?

As a matter of fact, that is neither the way I wrote it, nor the way I would consult anyone to go about writing it. On the contrary, I used an iterative approach. I started with a suite of tests that led me to the first implementation. Then I identified the problems and I felt dissatisfied with the implementation, which led me to refactoring. I used the suite of tests as a safety net and I started applying small modifications to the structure of the code, making sure that I did not break the tests after every such modification. With every change, I amended something, which got me closer to what I had in mind as a goal (an open-closed validation module).

There is no need to think of everything upfront. In fact, there is no need to think of anything upfront. Just get a working piece of code, as simply as you can, but don’t stop there. Don’t be satisfied with it. Study it. Identify weaknesses and strengths and refactor to make it better. Refactoring is a mighty tool in our software design arsenal. Use it to shape the code the way a software craftsperson would.

Conclusion

Implementing a solution to a problem can be easy, especially for a relatively simple problem. What is hard is to distance ourselves from our solution and improve it. However, as software craftspeople, we should train ourselves to identifying downsides and merits of architectures and code design decisions and even more importantly, take pains to address them.

Violating the Open-Closed Principle may seem harmless, but as the code base grows it can turn out to be an insurmountable obstacle to the project’s sustainability. There is no such thing as a perfect architecture, that can shield our code from every potential future change, but provisioning for reasonable changes and structuring the code respectively is part of our job, rather than nice-to-have.