The test should pass now. Oh, it still fails. Why is that? I think I’ve missed this edge case. I’ll fix it by adding this line, here. Great, it passed, but another one fails now. That’s weird. I guess that this line broke the other case. Never mind, I’ll add this line too and this should fix both of them. Oh, now I’ve broken a bunch of them.

Have you ever been in a situation like this? Do you relate to the train of thoughts? How long did it take you to get all the tests to pass? How did you feel when they finally passed? Creative, energized and ready to continue or relieved, exhausted and ready to take a break or call it a day? What if you had reverted the change as soon as it made a test fail and approached the problem from a different angle?

This is one of the key ideas behind test && commit || revert (TCR), a programming workflow born during a Kent Beck workshop (and also attributed to Oddmund Strømme, Lars Barlindhaug, and Ole Johannessen). In this blog post, I will try to provide an overview of TCR.

Before we delve into it, let me add a small disclaimer. I have only scratched the surface of TCR. I have only used it in playground projects, with the sole purpose of understanding it. I have not used it in production code and I am definitely not advocating for it in this post. The intention of the post is to let you know that TCR is a thing and merely present some of its trade-offs that I have discovered.

The main idea

During any typical programming workflow, we run the tests a lot. We definitely do so before committing the code. So, the idea behind TCR is that we should commit every time the tests pass. But there’s a catch. If we do commit every time the tests pass, we should also revert every time the tests fail. It’s simple but profound and powerful.

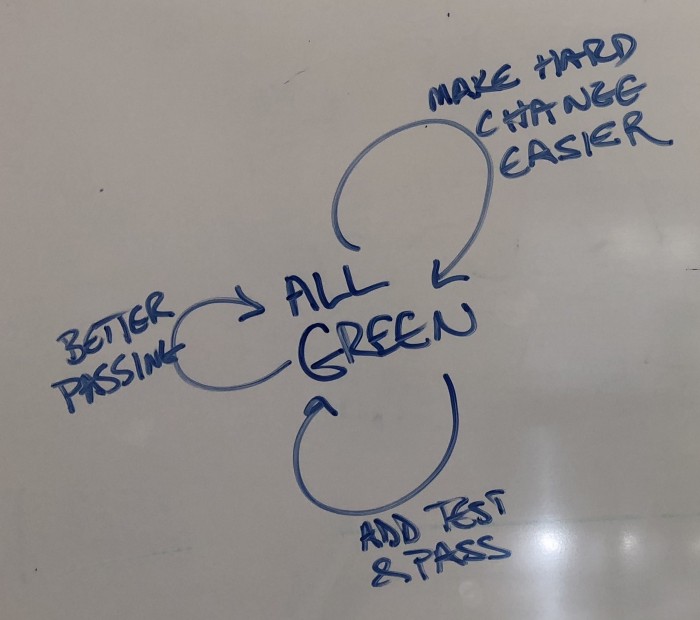

Applying these two constraints locks us in a cycle. Exactly like TDD does, just with a different cycle. Since a failing test automatically reverts the code, there is no red state. We always keep the tests passing and we always find ourselves in the green state, the only state there is.

source: https://medium.com/@kentbeck_7670/test-commit-revert-870bbd756864

Why should I try it

Now, I understand that TCR may sound extreme (to say the least). I can already hear the objections. “But I will be losing code”. “But I love the red state”. “But it sounds so frustrating”. “But why would I want to do that?”. These were also my first thoughts. So, let’s try to understand what do we stand to gain from giving TCR a chance.

Baby steps

If there was a single lesson to be learned from practising TCR it would be the following:

The only way to go fast, it to go well

This is a quote from Uncle Bob, which has shaped my way of thinking around writing code like few others.

The core idea behind TCR is moving in small steps. Moving in baby steps. Tiny steps. Small enough to be sure that they keep the tests passing. Small enough not to risk losing a bunch of code if a test fails. The philosophy is “what is the next, small, steady step that I can take towards my goal?”.

Moving forwards in small, seemingly insignificant steps can be surprisingly more beneficial than going back and forth.

Gamification

Practice TCR for 10 minutes and you can’t help but notice the gamification element. Causing a test to fail feels like making a mistake in a video game and having to start over again. Gamification makes us have fun. And when we have fun we tend to be more creative and we tend to come up with better solutions (this is just my intuition, it is not backed by any study that I know of). Of course, this coin has two sides, but we will discuss this in-depth later on.

Improves refactoring

Refactoring a piece of code takes discipline. It requires a series of small, confident steps. It requires keeping the tests green at all times. The truth is that, even with the aid of the IDE’s automated refactoring options, this is challenging.

I find that TCR can be immensely helpful during the refactoring process. Any modification that breaks the tests gets automatically reverted. Therefore, by definition, all refactoring moves keep the tests green.

But there’s more in it. Refactoring moves that break the tests get reverted. They do not “survive” into commits. Only the ones that keep the tests passing “survive”. They get committed and eventually pushed and merged. This rings a bell, doesn’t it? This sounds a lot like a natural selection process for refactoring moves. Just the ones that display useful qualities (keep the tests passing) make it into commits. The accumulation of the effects of this continuous feedback is bound to make us more skilled in the long run. Let’s not get too carried away with the metaphor, but I strongly believe that applying TCR when refactoring can really improve our refactoring skills.

A tool for understanding legacy code

TCR works wonderfully well as a learning tool. Assuming that we have a piece of legacy code that we want to understand. It’s natural that we start making assumptions when we read the code. Suppose we fire up the TCR script and express these assumptions as unit tests. If the assumption is correct, the test passes and we just learned for sure that the code does what we thought it did. In case the assumption was incorrect, the test fails and disappears. We learned what the code does not do. So, we just learned again.

This is like orally applying specification by example in a conversation with the author of the code. Except that the author might even be in a different company now. Except that there is way less room for a misunderstanding, as the specification is written in code. Except that we get to keep a comprehensive test suite when we are done.

I learned about this fascinating technique when I came across this video, which illustrates it wonderfully.

Downsides

Having listed some advantages, let’s also have a look at some inconveniencies that come with the TCR.

Losing stacktraces and test output

I feel that one downside is too obvious to ignore. This is losing the stacktrace of a failed test. It’s natural. When a test fails, we want to understand why it failed. However, since the tests get reverted automatically, the stacktrace disappears.

Perhaps there are ways around the issue, by carefully configuring the test command you use, but it was the very first thing that annoyed me when a test failed when I wasn’t expecting it.

This does not stop on stacktraces though. The test output in general is gone with the reverted code. It first bothered me when I used Spock’s @Unroll feature and a single case failed.

Unconvenient as it might be, this is part of the process. TCR urges you to approach the problem from a different angle, or maybe opt for a smaller step. Debugging a failed test completely defeats the purpose.

Commit messages

It should be obvious that practising TCR can easily create tens of tiny commits. Actually, it should do exactly that when done right. So, the questions that naturally follow are “what do I do with all those commits?” and “what about the commit messages?”.

These can be addressed in a number of ways. For instance, my preferred method is to add a default commit message (e.g. “WIP”). Then, when I reached the point in which I would originally commit if I was not using TCR, I would squash all these, tiny, WIP commits into a single one and reword it. Apart from this, there are other methods that would also work, like using the git diff list as the commit message.

Nevertheless, this constitutes a problem that should be solved and, one way or another, it’s an overhead.

Frustration

The alter ego of the above-mentioned gamification aspect is the irritation that TCR can cause you. The rational first reaction to witnessing the code you’ve been writing over the past few minutes (or seconds) magically disappearing in front of your eyes is frustration. Sometimes even anger. While gamification can make one more creative, frustration can lead to bad-tempered decisions and hasty solutions.

Unfortunately, this can lead to a vicious cycle. The more the code gets reverted, the worse your mood gets, which leads to more mistakes, which leads to the code getting reverted even more. Quite ironically, this is a good feature of TCR, because if you find yourself having your code reverted (say) 10 times in a row, perhaps that’s the best sign that you need to take a break.

In any case, I feel that this is perhaps the most interesting trade-off that TCR has to offer. The balance between having fun and feeling angry and disappointed is crucial. In other words, for TCR to be effective, sticking to the essence is key. And the essence is aiming for baby steps.

Open questions

A programming workflow it’s open to customization and experimentation by its nature. TCR, being fairly new (created in 2018), leaves plenty of room for both. Let’s examine some of the aspects that remain open.

Reverting tests

Writing a test only to have it reverted because it failed can be discouraging. Especially for people with a strong TDD background, who have worked hard to install the habit of writing a failing unit test first. This can be particularly disturbing for them. Maybe this is the reason why a variation suggests that the tests should not get reverted as part of the TCR process. In other words, when a test fails, the production code should get reverted, but not the tests.

I strongly believe that different approaches may work better for different people. TCR is a tool. It’s merely means to an end and not an end in itself. So, I have deliberately chosen to include this topic in the open questions. I believe that either approach will work. So, some people will choose to revert the tests along with the production code and some people will not do so.

What happens with pushing

We have already discussed the issue with the numerous, tiny commits, but when does the code get pushed during this workflow? Again, this is a matter of choice. Manually pushing after a bunch of small commits will work fine. Exactly like automatically pushing along with every tiny commit. The former diminishes the sense of “continuous delivery” that comes with TCR while the latter most likely requires a rebase and force push. The issue with the commit messages has to be resolved in either case. So, again, I would suggest customizing it to your preference.

Setting up the environment for TCR

Practising TCR requires a little bit of setup. There should be an automated way to observe the source files and detect changes, run the tests and, depending on the outcome of the tests, either commit or revert the code. There are various ways in which this can be achieved. Personally, I used the following bash scripts:

- a

watch.shscript that observes the source code, detects changes on it and triggers the TCR script.

#!/bin/bash

while true; do

inotifywait -r -e modify src

./tcr.sh

done

- the

tcr.shscript, that holds the base logic of TCR:

#!/bin/bash

source "scripts/test.sh"

source "scripts/commit.sh"

source "scripts/revert.sh"

test && commit || revert

- the

test.shscript, which executes the unit tests

#!/bin/bash

function test() {

echo "Testing changes..."

./gradlew test

}

- the

commit.shscript

#!/bin/bash

function commit() {

echo "Committing and pushing changes"

git add . && git commit -m "WIP" && git push

}

- and the

revert.shscript

#!/bin/bash

function revert() {

echo "Reverting changes"

git checkout .

}

I have created a playground github repository. It is set up for Kotlin and Spock and serves me for experimenting with TCR, but feel free to either grab the bash scripts or fork the repository and use it to play with TCR.

Conclusion

TCR provides some exciting and fresh ideas. It focuses on small, steady steps, which accumulate to create progress. It gamifies programming and, among other things, it can improve refactoring and work as a tool for understanding legacy code.

There are disadvantages to be considered, such as losing the stacktraces and output of failed tests, dealing with countless tiny commits and dealing with frustration. There are also a lot of open questions, like whether or not tests should get reverted along with the production code or when should the code be pushed.

TCR sounds extreme, but I am sure that people were thinking exactly the same about TDD when it first came out.